The Right to Know: Egyptian Bill is Toothless

In connection with the Egyptian Constitution’s guarantee of citizens’ right to access information, data, and official documents,[1] the Supreme Council for Media Regulation held a press conference on October 25, 2017,[2] to announce that it had drafted a “freedom of information” bill as one of the laws complementing the Constitution.[3] The law will be the first in Egypt’s system of legislations to regulate the circulation and means of disclosing data and information.

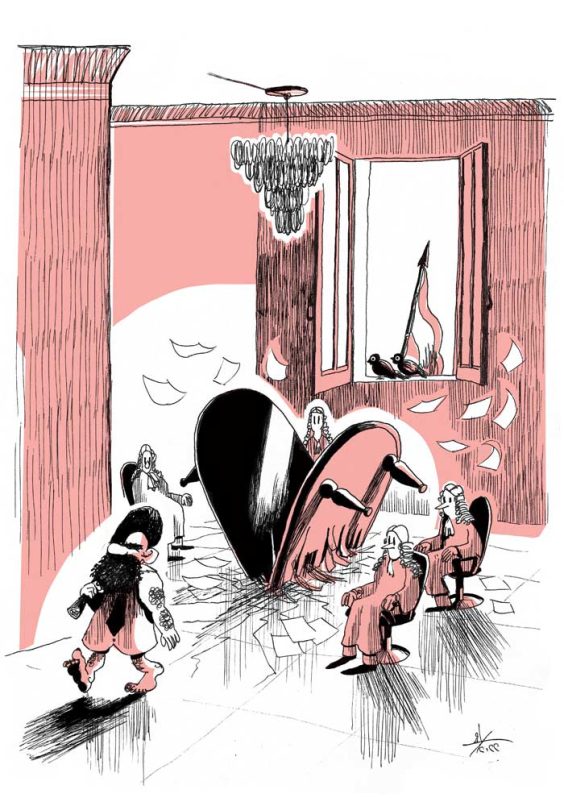

Disappointingly, the provisions of the proposed bill hollow the right to information and data of its substance. This suggests that the Supreme Council for Media Regulation has yet to recognize the importance of freedom of information.

Flexible Definitions and Abundant Exceptions

The first chapter of the bill defines some of its terms, such as “information”, “data”, and “disclosure”.[4] These definitions are to a large extent conventional and reasonable.

Additionally, Article 16 excludes a number of types of data and information from those which must be disclosed.[5] The most important are “data and information pertaining to national security”, “data and information connected to commercial and industrial secrets”, and “data and information connected to commercial negotiations”. However, there is no explanation of the intended meaning of “commercial and industrial secrets”, the commercial negotiations about which information may not be disseminated, or the parties to these negotiations. Hence, this article can be used to withhold anything related to industrial or commercial activity in Egypt. This deprives this law of its substance and basic purpose as a guarantee of freedom of information. Furthermore, Article 17 allows the bodies addressed by the law to refuse to disclose information and data that they obtain “from another state or an international organization when there is mutual trust between the two parties and whose disclosure would damage relations with the state or international organization”, a matter not precisely defined.[6] What damage is meant? Who has the power to assess such potential damage? This exception could allow a complete blackout on all documents concerning Egypt’s relations with all other countries and the international organizations that usually supply state bodies with periodic information, data, and statistics in a number of areas, such as health and education.

The bill also stipulates a timeframe for this ban on certain information and data. Under Article 18, “the protection established by the provisions of this law ceases for the disclosure of data and information older than 30 years”. This measure resembles most Western legislations governing the circulation of information and disclosure of documents.[7]

Regarding the second chapter of the bill (“the right to access information”), Article 7 stipulates that “the data and information accessed may not be used for anything other than the purpose for which it was collected, nor as evidence in a crime or as a basis for any other legal action”. This is incomprehensible. How could data obtained in accordance with this law, and exonerating or condemning a person implicated in a crime not be accepted as evidence? The prohibition on using this data or information as a basis for any other legal action is similarly unjustified.

National Security: The Legislators’ Gateway for Withholding Information

Even though international law[8] and the Egyptian Constitution recognize the right to the freedom to circulate and access information, and the bill’s explanatory memorandum mentions recognition of this right in accordance with international standards,[9] the bill ties it to national security.[10] The concept of national security is obscure as its definition differs from one law to another. Under the present bill, “national security matters include all security-related information and data that the competent body deems confidential, as well as the investigations conducted by intelligence, control, and security bodies”. This definition gives all the bodies addressed by this law broad power to deem information they do not want to be disseminated or accessed confidential. However, the law regulating communications, for example, defines national security as encompassing “anything related to the affairs of the presidency of the republic, the Armed Forces, military production, the Ministry of Interior, general security, the National Security Body, the Administrative Control Authority, and the apparatuses subordinate to these bodies”.[11] This definition based on national security protects entire institutions from scrutiny under its aegis. It differs from the definition stated at the beginning of this bill. When it comes to the circulation of information, which definition will prevail?

Non-Deterrent Punishments

In the bill’s seventh chapter (“Crimes and Punishments”), Article 28 stipulates a number of punishments for violating its provisions. The bill imposes “a fine from EGP 3,000 to 10,000 [US $170 to $565], on anyone who refrains from providing the requested data without an acceptable justification, provides incorrect data, or uses the data or information accessed for a purpose other than that for which it was collected”. It also punishes anyone who “destroys records or books pertaining to data and information held by a body addressed by this law with up to one year of imprisonment and a fine ranging from EGP 5,000 to 20,000 [US $285 to $1130] or one of these two punishments”. These punishments are comical as they do not match the gravity of the crime of refusing to provide information or destroying records and books. The inclusion of only moderate fines in most cases and the absence of harsh punishments shows that the legislators were not serious about punishing people who violate this law or were at least not convinced of the importance of access to information and its free circulation.

At the same time, Egyptian legislators have stipulated a number of custodial punishments for less serious crimes. For example, the new health insurance law stipulated imprisonment for at least six months for whosoever gives incorrect information or refuses to give the information stipulated in that law.[12] This reflects the Egyptian legislators’ vigorous use of the law to deter any error by citizens while largely tolerating errors by the state or public servants.

Does the Bill Help Consolidate the Right to Know and Press Freedom?

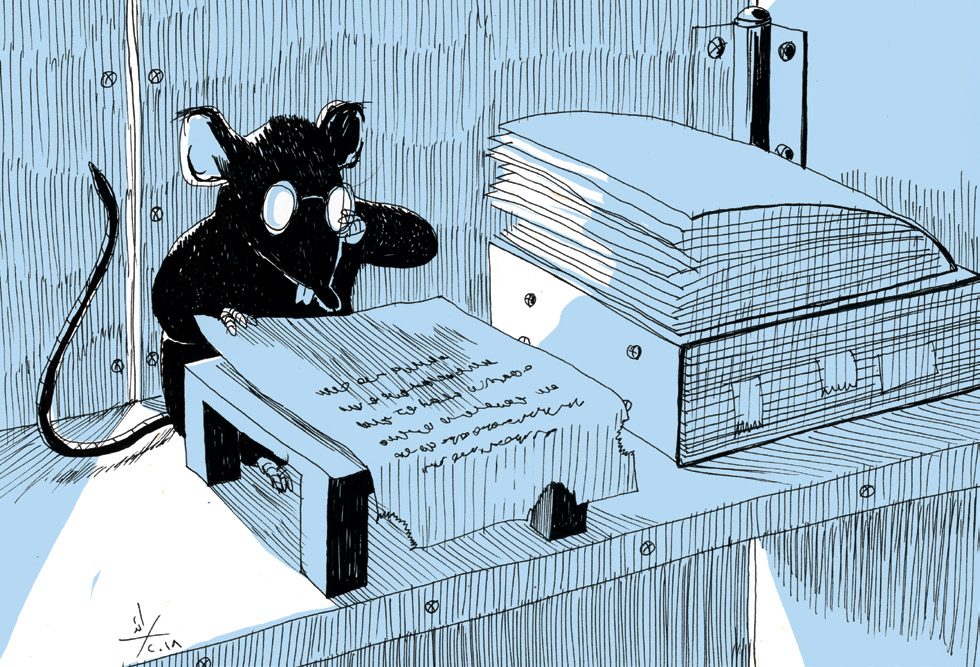

The right to information is closely connected to other rights, such as the right to know. The right to know is considered the primary aim of the circulation of data and information, for it allows citizens to monitor the performance of the state’s various bodies and stay informed of their policies and budgets, leading to more accountability and less corruption. This right is also an essential tool for researchers in various fields interested in viewing the various historical documents concerning the most important periods in Egyptian history, which are treated as military secrets even though they belong to the Egyptian people.[13] Freedom of information also greatly affects press freedom, and the absence of data and information obstructs the watchdog and awareness-raising role vested in media bodies.

Hence, this law will have a severe negative impact on citizens’ access to data and information, which infringes on their right to know, and press and publication freedom in general. The bill could prevent them from accessing a lot of information considered a matter of national security by the competent bodies, as well as matters related to commercial and industrial affairs, which would automatically impact publication and media freedom in relation to these issues.

On the other hand, the Egyptian administrative judiciary has, in multiple rulings, recognized citizens’ right to know and emphasized freedom of information and data. It has also called upon legislators multiple times to intervene and enact a clear law regulating the entire process of circulating information. The most notable of these rulings may be the one obliging the government to disclose settlements made on state contracts concerning public funds.[14]

Furthermore, the State Council addressed the relationship between freedom of information and press and publication freedom in its ruling nullifying the gag order on the case of fraud in the presidential elections.[15] The ruling stated that withholding true information from citizens and banning the media from publishing on a given subject could deprive them of their right to access accurate information. In another ruling, the Court of Administrative Justice used the new constitutional text on the right to access information – for the first time – to oblige the Amiria Press Authority to make sufficient numbers of the official gazette available throughout the country and provide free access to the legislations published in it on this body’s website.[16]

Hence, given the provisions of the current bill, the judiciary is still ahead of the legislators when it comes to guaranteeing the right to access and circulate information.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

[1] Article 68 of the Egyptian Constitution states,

Information, data, statistics and official documents are owned by the people. Disclosure thereof from various sources is a right guaranteed by the state to all citizens. The state shall provide and make them available to citizens with transparency. The law shall organize rules for obtaining such, rules of availability and confidentiality, rules for depositing and preserving such, and lodging complaints against refusals to grant access thereto. The law shall specify penalties for withholding information or deliberately providing false information. State institutions shall deposit official documents with the National Library and Archives once they are no longer in use. They shall also protect them, secure them from loss or damage, and restore and digitize them using all modern means and instruments, as per the law.

[2] Under Law no. 92 of 2016 (On Issuing the Law on Institutional Regulation of the Press and Media), the Supreme Council for Media Regulation is the body responsible for regulating audio, visual, and digital media and printed, digital, and other kinds of press.

[3] Bill on the Freedom to Circulate Information. The bill was published online by Youm7 on October 25, 2017.

[4] Article 1 of the bill.

[5] Article 16 of the bill states,

The data and information that must be disclosed does not include:

a) Data and information pertaining to national security.

b) Data and information connected to industrial or commercial secrets.

c) Data and information connected to commercial negotiations.

d) Investigations subject to a judicial gag order.

e) Personal information of workers in the bodies addressed by this law.

f) Personal or individual information protected by other laws.

This prohibition does not apply when the competent court has issued a decision to disclose the data and information subject to the decision issued in this regard.

[6] Article 17 of the bill states,

The bodies addressed by this law may refuse to disclose information and data in their possession in the following cases:

a) Information that the body obtains from another state or an international organization when there is mutual trust between the two parties and whose disclosure would damage relations with the state or international organization.

b) Information whose disclosure would breach a legal obligation between any of the bodies subject to this law and a third party or expose personal information pertaining to it [the third party] unless the third party relinquishes this right or has explicitly consented to this disclosure.

c) Information whose disclosure would obstruct the detection of a crime, the arrest or prosecution of the offenders, or investigation procedures.

[7] “Government transparency depends on freedom of information”

[8] The right to freedom of information was recognized in the first session of the United Nations’ General Assembly via Resolution no. 59 of 1946. The resolution stipulated that the freedom to access information is a basic human right. Moreover, Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights obliged states to guarantee the right to freedom of expression, including seeking, receiving, and imparting information and ideas through any media. Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights recognizes the right to freedom of information as found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

[9] Page 3 of the bill’s explanatory memorandum.

[10] Article 86 of the Egyptian Constitution states, “Preservation of national security is a duty, and the commitment of all to uphold such is a national responsibility ensured by law. Defense of the nation and protecting its land is an honor and sacred duty. Military service is mandatory according to the law”.

[11] Clause 19 of Article 1 of Law no. 10 of 2003 (On Regulating Communications).

[12] Parliament has passed this law, but it has not yet been published in the official gazette. Article 62 states, “Whoever gives incorrect data or refrains from giving the data stipulated in this law or its implementary regulations shall be punished with no less than six months of imprisonment and a fine from EGP 2,000 to 10,000 [US $150 to $565] or one of these two punishments if doing so results in wrongfully obtaining money from the Authority”.

[13] See the series of articles titled “Khamsun ‘Amman ‘ala Hazimat Yuniyu” (Fifty Years on from the June Defeat), wherein Egyptian historian Khaled Fahmy mentions the withholding of all documents concerning that period. The documents are stored in the military records archive, and the public cannot view them. https://khaledfahmy.org/ar/

[14] Court of Administrative Justice ruling on case no. 59439 of judicial year 67, hearing of November 17, 2015.

[15] Court of Administrative Justice ruling on case no. 2402 of judicial year 69, hearing of January 19, 2016. This case was filed to annul the gag order that the public prosecutor issued on October 14, 2014, on news about the investigation into incidents of fraud in the 2012 presidential elections.

[16] Court of Administrative Justice ruling on case no. 63089 of judicial year 66, hearing of June 24, 2014.