Denying Syrian Refugees Status: Helping or Harming Lebanon?

At the beginning of 2015, the General Directorate of General Security (“General Security”) modified the conditions of residence for Syrians pursuant to the policy -adopted by the Council of Ministers- of “reducing the numbers”. In fact, this policy did not “reduce the numbers”. Rather, first and foremost, it stripped more than 70% of Syrians residing in Lebanon of their legal residence papers. These Syrians became invisible to the Lebanese authorities and lost many of their rights.

In the absence of a comprehensive plan for managing the Syrian refugee crisis, why does Lebanon continue to implement a policy that is not achieving its stated goals, and that is harming the country’s public interest and the rights of the refugees?

Residence Conditions Do Not Protect Refugees

The decision that Lebanon’s General Security issued at the beginning of 2015 not only stopped incoming refugees from entering at the borders in line with the “Syrian Displacement Policy” adopted by the Council of Ministers on October 24, 2014. Rather, the decision also modified the conditions for granting residence permits to the Syrians already present in Lebanon. It imposed harsh and costly restrictions on renewing residence documents, restrictions that do not account for the protection needs of the refugees. Hence, the Syrians unable to return to Syria or leave Lebanon for another country fell victim to these restrictions. This decision therefore did not reduce the number of Syrians actually present in Lebanon; rather, it merely reduced the number with legal residence in an attempt to encourage them to leave Lebanon, and to circumvent the principle of non-refoulement that Lebanon is obligated to uphold.

Because of this decision and the way it has been applied, Syrians in the most need of legal protection have been denied residence permits; and, these permits have been restricted to those in whom the state sees some economic benefit, such as capital-owners and workers in the agriculture and construction sectors. Until 2014, Lebanon had an entry and residence policy that did not distinguish between refugees and other persons from Syria. The new post-2015 policy discriminated between them, but deprived the refugees of the legal protection afforded by legal residence instead of guaranteeing it.

In fact, well-off Syrians could obtain temporary residence permits (based on their ownership of properties or leases in Lebanon, and their proof of a secure livelihood), as could students and the children and husbands of Lebanese women. Others could only obtain a residence permit based on a “pledge of responsibility” from a sponsor. Hence, a Syrian citizen’s stay in Lebanon became dependent on the will of a Lebanese person. Sponsorship is a practice employed (without any legal text) to regulate foreign labor in Lebanon and is associated with risk of exploitation. The 2015 instructions/decision introduced this practice and its associated risks into the regulation of Syrians’ legal status, even in cases where the relationship between the prospective sponsor and the Syrian national is based on kinship or friendship. Government requirements stipulating that refugees must demonstrate proof of means of livelihood or availability of sponsor further blocked the refugee’s ability to obtain residence based on refugee status (which the Lebanese government calls “displaced” status to deny the reality of forced asylum). Additionally, the obscurity and arbitrariness surrounding the application of the new conditions and the inconsistency between the practices of the various General Security offices further complicated the processes for obtaining residence. Also, residence and paperwork fees formed an obstacle to renewal as 70% of the refugees are living below the poverty line. Many organizations have documented these difficulties.

Consequently, a broad segment of Syrians has been forced to remain in Lebanon without legal residence. The United Nations estimates that the number of Syrian families wherein no member has legal residence exceeded 70% in September 2016. This percentage climbs above 90% in the Beqaa, Baalbek-Hermel, and Akkar governorates and drops to approximately 57% in the Beirut and North governorates.

Manufacturing Syrians’ Vulnerability: Harming Lebanon’s Interest

Hence, with the stroke of a pen, hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees were forced to live in Lebanon outside of the law, and its protection. Their mere presence in Lebanese territory became cause for arrest and prosecution. They also became susceptible to exploitation by state and non-state actors. Lack of legal status poses a serious challenge to everyday life and access to basic rights. In particular, fear of arrest limits the refugees’ mobility, which affects their ability to secure a living, enroll their children in school, and resort to the police and the courts. In fact, studies have shown an increase in the number of children who, instead of attending school, are forced to work to secure the livelihoods of families deprived of residence permits.

Depriving most Syrians of legal status puts them in a vulnerable position and isolates them in the informal economy, alongside the most marginalized Lebanese. The poor people of both nationalities then compete over the meager work opportunities. This too opens the way for influential people to abuse and exploit them and for harsh working and housing conditions to be imposed upon them, while limiting their ability to demand justice in order to demand their rights. Many organizations have documented the negative repercussions, especially on child education, protection of women, and livelihood security.

The harm does not appear to be contained to the dignity and rights of the Syrian refugees. Rather, it also encompasses the security situation and the proper functioning of the Lebanese state institutions. Hundreds of thousands of people have become invisible to the authorities, absent from the state’s registers, and outside of the state’s purview. There is no official, unified census for the Syrians and their places of residence in Lebanon. Is it in Lebanon’s interest for tens of thousands of people forced to stay in its territory to be outside its purview?

Furthermore, the lack of legal status also weakens the Syrian refugees’ trust in Lebanon’s security agencies and their ability to protect refugees, as the latter fear arrest simply for being refugees. How can persons without legal status report crimes that they witness or fall victim to, when any interaction with the security agencies will inevitably lead to their arrest? On the other hand, the rise in the number of Syrians forced to violate residence conditions has put more pressure on the state institutions concerned. The General Security’s stations are congested with Syrians whose documents are in bureaucratic limbo, and the Internal Security and General Security’s jails are crowded with Syrians temporarily detained for not possessing valid residence permits. Similarly, the courts are inundated with trials of offenders. This added pressure stems not from the rise in the number of refugees, but from the state’s policy of forcing them to violate the new residence regulations.

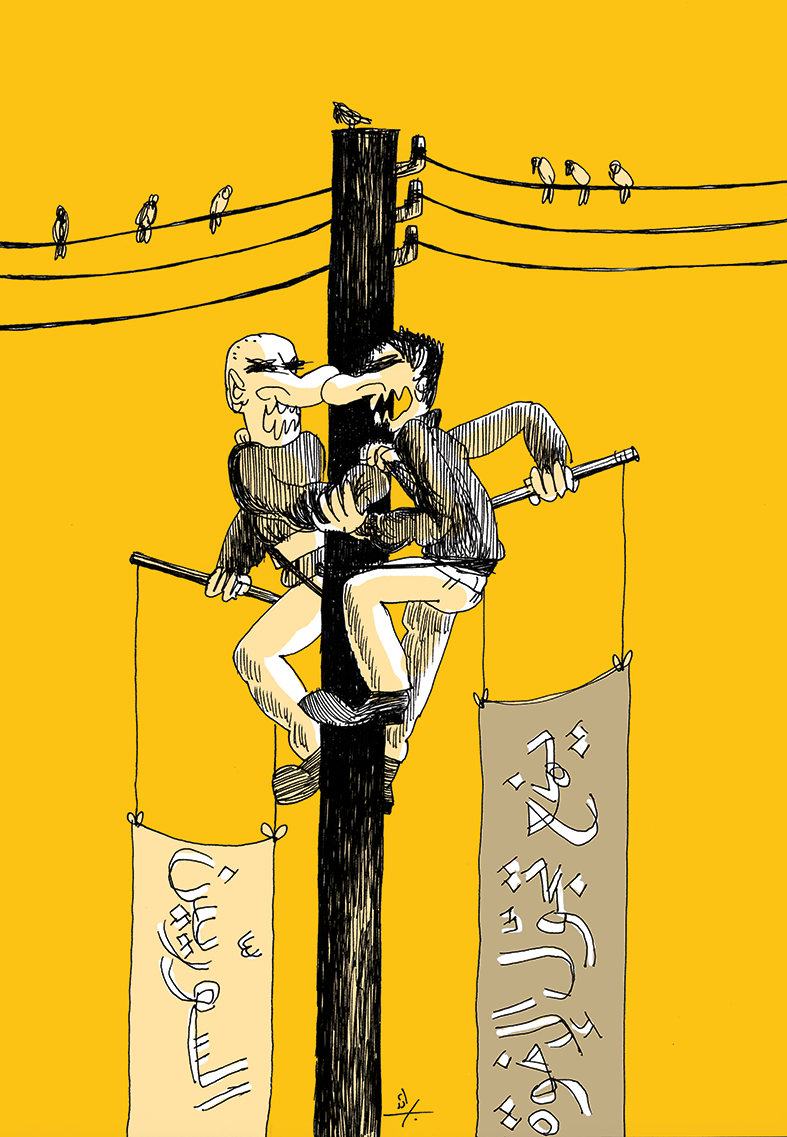

This policy therefore appears unjustified from both a humanitarian and security perspective, and is akin to the policy of “manufacturing vulnerability” that aims to deprive groups of people of basic rights in order to deny their existence, or facilitate their exploitation. How does the state officially justify this policy?

The State’s Justifications: The Catch-22 of No Settlement and No return

The official justification for this policy appeared in the state’s position in the judicial case filed against the General Security’s instructions, concerning the entry and residence conditions for Syrians. In 2015, one Syrian refugee, aided by The Legal Agenda and the Frontiers Ruwad Association, filed a challenge to these instructions in the State Council. The challenge cited the instructions’ contravention of Lebanese law and bilateral and international agreements, and the principles of asylum that Lebanon is bound to uphold. This recourse to the judiciary is an attempt to induce Lebanon to adopt more rational policies in its management of incoming refugees, and to cease ignoring legal standards as a result of other crisis-related concerns.

In the context of this case, the state argued that these new instructions aim to put all Syrians under state purview to protect Lebanon’s interest, and to protect the refugees from exploitation. This position is completely divorced from reality as these instructions clearly led to an outcome diametrically opposed to the stated goals, as I detailed earlier. Similarly, putting these arguments in the context of previous practices toward refugees from Palestine, Iraq, Sudan, and other countries confirms that, in reality, this policy actually aims to prevent refugees from remaining in Lebanon. It is a means of pressuring the refugees to leave Lebanon, and of pressuring the international community to fulfill its responsibility to provide them with durable solutions over the long-term. Hence, the political consensus in refugee issues appears to be based on a set of “Nos” –such as rejecting camps, work, and residence permits– and to in practice reject the refugees’ presence legally, despite their de facto presence.

Therefore, this policy is not based on legal, political, security, or humanitarian grounds. Rather, it is based on ideological grounds relating to rejecting permanent settlement of refugees, and maintaining the demographic equilibrium of the [confessional] constituents of Lebanese society. In other words, it is based on the ideology that favors the rights of sects over the rights of individuals, and that forms the official argument for denying Lebanese women the equal right to pass on their nationality to their husbands and children. In tandem with denying settlement, an official discourse has spread in Lebanon stressing the need for the refugees to “return” to Syria, ahead of any sign of a political resolution on the immediate horizon. This discourse culminated in the inclusion of the “swift return” clause in the [new] president’s oath speech, and in the minister of labor’s call for a transition from managing the refugee crisis in Lebanon to managing the refugees’ return to Syria. In this regard, the most concerning matter is that some political parties are rejecting the principle of “voluntary” return, and adhering only to the principle of “safe” return. Such a stance exacerbates the status of the Syrian refugees in Lebanon, and increases the risk that they would be forcibly deported to Syria in the future.

But these demands face several obstacles. The first is the inconceivability of an imminent return to Syria and the risks associated with large numbers of Syrians returning (or being returned) before a political solution involving all components of Syrian society, both inside the country and in the diaspora, has ripened. Such a return could result in a new wave of displacement from Syria. These demands also clash with the position of the international community, particularly the donor countries and United Nations organizations which, given that a return to Syria is presently impossible, are calling upon Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey –the countries of first asylum– to absorb the refugees. Of course, these parties aim to prevent the arrival of more refugees in Europe, and to reduce the refugees’ reliance on meager international aid by encouraging self-sufficiency.

In such a context, Lebanon’s signing of new partnership priorities with the European Union on November 15, 2016, is among the signs of a potential change. Lebanon –the first country to sign such an agreement– has committed to improving the status of Syrian refugees, in exchange for redoubled economic and financial support from the European Union. Via this agreement, Lebanon also pledged –as it did previously at the London conference– to relax the terms of temporary residence for Syrians until conditions for a safe and voluntary return to Syria arise. Does this development signal that the state will improve its management of the Syrian refugee crisis in a manner that balances concerns for Lebanon’s stability with respecting the dignity of the Syrian refugees?

Mapped through:

Articles, Asylum, Migration and Human Trafficking, Lebanon

Related Articles