The Lebanese Judiciary Laid Bare: Changing Tides and Trials

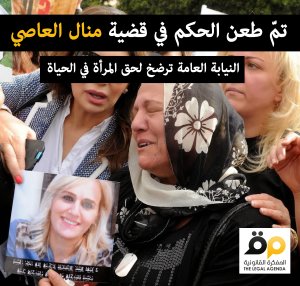

The announcement of the ruling in the case of Manal Assi, which reduced to five years the sentence of imprisonment of her husband for savagely murdering her, provoked a wave of condemnations from Lebanese civil society, the media, and politicians.[1] Several civil society efforts converged to pressure the Public Prosecution to appeal the ruling. These included the holding of two sit-ins in front of the courthouse, the organization of a petition, and the shooting of a short film. A number of television stations and newspapers dedicated many segments, including leading stories on the evening news to explain the ruling’s flaws and calling for its appeal. On its part, The Legal Agenda dedicated the cover of its July issue to the topic, using the telling title “The Return of the Macho [al-Batal]” in reference to the return of machismo and values associated with bullying vulnerable groups, particularly women. The response to the ruling transcended civic activism to also encompass political movements, thus creating a potentially unique precedent.

On the one hand, the Justice Commissariat of the Progressive Socialist Party held a meeting with the bodies for youth, rights, and women of more than ten parties. At the meeting’s conclusion, the participants affirmed their “categorical rejection of any jurisprudence or course that brings honor crime back into force, and reestablishes it in reality after it was rectified in law”, and expressed their surprise that the Public Prosecution was behaving like an “indolent bystander” with respect to its role representing the community and its interests (August 16). On the other hand, Phalange party MP Samy Gemayel directed two letters to the Minister of Justice and the Supreme Judicial Council, calling upon them to rehabilitate the Lebanese judiciary’s image and realize justice in the Manal Assi case (August 17). The popular pressure compelled [acting] Minister of Justice Ashraf Rifi to ask the Public Prosecution in the Court of Cassation to appeal the ruling if legal factors permit it to do so.

While the judges who issued the ruling remained silent pursuant to judicial customs, it was remarkable that the Media Office of the Supreme Judicial Council refrained from adopting any position given all of the above. Just comparing this silence to its statements on a similar case (that of Roula Yaacoub), wherein it rejected the use of the media “as a means of pressure to interfere with the proper functioning of judicial work”, is enough to reveal the change occurring with regard to media criticism of court rulings. The council’s silence on the Assi case suggests that it has become more cautious about unconditionally defending judges from criticisms, lest its stance reflect negatively on the judiciary as a whole.

Judicial Schisms: The Pioneering Judge is Not Alone

Consequently, for judges, the Manal Assi case was an important signal of a fundamental change in the way that their rulings are approached. These rulings may now enjoy widespread social debate that subjects the judges, their positions, and their jurisprudence to accountability that could mark their entire judicial career. While judges have previously received several messages about the need to avoid infringing the interests of the ruling regime under pain of being functionally marginalized (the John Qazzi incident discussed below is symbolic of such marginalization), the Assi case has sent them a different, perhaps contrary warning. Namely, they must deal wisely and cautiously with social issues, at least the ones that have come to enjoy widespread public attention.

Besides strengthening media accountability, this change is also likely, in particular, to end the hegemony of the conservative stream inside the judiciary and create enormous potential for the development of the streams that are more open to, and supportive of social causes. Hence, although many pioneering interpretative judgments have resulted in a series of repressive measures to overturn them and marginalize the judges that issued them, the social penetration into judicial affairs is now capable of providing greater protection for said judges, and of potentially turning them into role models in the performance of judicial jobs. Of course, this was corroborated when the Public Prosecution in the Court of Cassation was compelled to respond to the demands to appeal the ruling.

To realize the importance of this change, we need only recall the course that the famous case of Lebanese woman Samira Soueidan took in 2009 after the First Instance Court in Matn (presided over by John Qazzi) defied the ruling authorities by granting nationality to her children born to a deceased Egyptian husband. Most significantly, the case witnessed the emergence of one of the most prominent schisms in the history of the Lebanese judiciary, one that quickly ended in the dominance of one of its two sides. On one side was the court’s President John Qazzi, who came to symbolize a judge who seeks via his or her jurisprudence to strengthen the justice system and promote human rights. On the other side was the president of the Court of Appeal chamber that examined the appeal against Qazzi’s ruling, Mary Denise Meouchi. Meouchi represented the traditional judge who sticks to their boundaries and to serving “the law” and, in practice, the legislature that produced it (i.e., self-restraint).

While the first instance decision interpreted the Law of Nationality in light of the constitutionally stipulated principle of equality between the sexes, and the principles of international law and the human rights charters ratified by Lebanon, the Court of Appeal in Mount Lebanon went the opposite direction. It deprived judges of any power to use any of the aforementioned bases when applying laws. Meouchi had no qualms about stating that with the establishment of the Constitutional Council, judges lost the right to set aside a domestic law on the basis that it contradicts an international covenant or agreement. This interpretation reflects an extraordinary stance that deprives lawyers, as well as activists, of the most important legal weapon for advocating social causes, namely international human rights conventions. More importantly, it turns judges into prisoners of the laws desired by the legislature, and hence into servants of said legislature, by barring them from making interpretative judgements.

To complement the above, the reigning system took measures against Qazzi himself. These measures began with transferring him without his consent to a position wherein making interpretative judgements is difficult, and culminated in barring him from speaking at conferences and referring him to the Judicial Inspection Committee on account of the speech he delivered upon receiving a human rights prize in 2009. In contrast, within months of issuing her ruling, Meouchi acquired one of the most important judicial positions –the presidency of the Legislation and Consultation Committee– which she still occupies today. Although the media and civil society organizations applauded Qazzi when he issued the ruling, a dubious silence prevailed when the measures against him were taken one after another. This silence reflected a different approach to social interaction with judicial processes, one that views the judiciary’s actions as important events that occur in isolation of social processes. According to this approach, we may applaud or criticize said actions, but neither the media nor social stances play any role in crafting or protecting them.

This approach is precisely what seems to have changed given the public discourse in the Manal Assi case. Several parties behaved as though they are a fundamental partner in the call for annulment. While the authorities’ efforts had successfully subdued the Judge Qazzi model (without permanently eliminating its specter) and restored the dominance of the traditional judge model, the discourse in the Assi case went the opposite direction. It resulted in the retreat of the conservative model, which seemed totally incompatible with the justice to which influential social forces aspire.

Another schism has thus far remained more closely guarded because of the social sensitivity of the issue concerned, namely the punishment of homosexuals. This schism emerged from the present judicial divide over the interpretation of Article 534 of the Criminal Code, a divide that three judges illustrated when they ruled that the phrase “sexual intercourse contrary to nature” is inapplicable to homosexual relationships.[2] This schism took on a remarkable dimension when the third ruling was issued, paving the way for the two precedents from years earlier to be turned into universalizable jurisprudence and hence topple the penal system in this area. Facing this possibility, the conservative forces appeared to be preparing to take swift measures against this “rebellion” to prevent its expansion. The Catholic Media Center organized a conference on what it labeled sexual “perversion”, which saw a judge introduced as a representative of the Supreme Judicial Council invoke the genesis narrative (Adam and Eve) to call attention to the duty of the (traditional) judge to apply the law criminalizing homosexuality.[3] Similarly, on June 7, 2016 –approximately forty days before the Criminal Court in Beirut issued its ruling in the Manal al-Assi case– the same court issued a reasoned ruling that deemed homosexuality a crime.[4] The grounds of the ruling appeared to respond to all of the arguments made in the three aforementioned rulings, thus stripping them of all legitimacy, just as occurred in the Soueidan case. It is also remarkable that the Beirut Criminal Court appeared to be in complete harmony with the Jdideh Court of Appeal when it came to stripping judges of the capacity to apply the human rights conventions and hence to make interpretative judgements.

According to the court, these conventions are directed solely at the legislature. It is up to the legislature to amend the laws, and judges are under no circumstances authorized to apply said conventions directly. Naturally, the reformist social forces once again found themselves faced with an important obligation to defend judges’ freedom to make interpretative judgments against the discourse, aimed at depriving them and society as a whole of said freedom. The more these forces succeed in using public discourse and the discourse inside the judicial institutions to protect judges’ right to form jurisprudence for the good of society, the more this “rebellion” can expand and force a deeper schism that is difficult for the conservative current to quash or contain and that will hopefully result in the rebellion’s triumph.

The Judiciary Appeals to Public Opinion

Alongside the discussion occurring about these social issues, an equally significant event –namely the case pertaining to the auctioning of airport car parks– revealed the extent to which judges are prepared to overcome their wariness of the political class, and its interests in order to combat corruption in public administrations. The State Council addressed the interference in the results of this auction and issued a decision voiding them. After the administration refused to implement said decision, the council’s President Shukri Sader opted to appeal to public opinion. He was content to appear twice successively on the evening news on LBC, the most viewed television station, to accuse the ruling class of not implementing rulings and thereby jeopardizing the workings of the public institutions and treasury.[5] Adding to the significance of these statements, they were made by a judge whose jurisprudence and opinions have usually reflected reservations about entering a direct confrontation with the ruling class. Among the most important of these stances is his dismissal of cases on the basis that they are popular cases, which in practice immunizes a significant number of obviously illegal decisions against judicial review.[6] His new stance signals a change among some of the most reserved judges. Another important sign of this change is the anger that the Minister of Public Works and Transport expressed in his press conference on August 17, 2016, wherein he appeared to be in disbelief that a judge could confront him in such a manner. His statement that his problem “is not with the justice [system], but with some people who think that they’re its personnel” was very telling. He seemed to be sorting justice personnel into two groups: the first –justice workers– includes judges who respect the ruling class’ red lines, or at least know their boundaries and therefore avoid of their own accord any legal or media confrontation with said class’ prominent figures. The second group do not deserve to be “justice personnel”. It consists of judges who forsake the duty of restraint in order to use their rulings to publicly confront the ruling authorities.

According to the minister, the involvement of these judges in such a confrontation shows their bias against the public administration, which justifies stripping their decisions of legitimacy and openly refusing to implement them. The minister thus seemed to draw from what he deems to be a judge’s rebellion against a politician the legitimacy to declare that said judge is rebelling against the judiciary. Although the social and media responses to the minister’s grave attitude remain limited, the severity of the clash clearly shows the importance of the change occurring, namely the judiciary’s turn towards appealing to the public when confronting “the politician”. This change will necessarily be very important to legal critics (including The Legal Agenda) when it comes to describing the judiciary’s relationship with “the politician” and, in particular, its efforts to consolidate its role and standing.

Media Monitoring: The Limits of Responsibility

Alongside the interplay occurring in these cases, which showed the increasing presence of court rulings in the media and its positives effects on social issues, there was another court case that provoked notable media coverage: namely, that pertaining to the alleged rape of the child Ibtisam in Tripoli. In summary, a girl accused three youths of gang raping her, only to later retract her statement and say that the sex was consensual. Irrespective of the veracity of the allegation or its retraction, the case revealed the extent to which women suffer when it comes to their private affairs. If the allegation was true, the retraction reveals the amount of pressure that a woman may face to relinquish her rights. If the allegation was false, the fact that it was filed reveals the tragedy of women who may find themselves unable to bear the burden of their sexual freedom. Whatever the case, the media generally went astray in its treatment of the case as several outlets committed two equally grave errors.

Firstly, the presumption of innocence was violated as the youths accused were openly condemned and their photos published. Consequently, the mother of one of them died of shock. This death showed that violating the presumption of innocence can kill, but the incident, despite its gravity, did not stop any of the media outlets. Furthermore, the Tripoli Bar Association did not play a corrective role as a custodian of the right of defense; instead, the organization’s president Fahd Mokkadem rushed to adopt a populist stance that went a step further in the violation of the presumption of innocence. Not only did he condemn the youths in advance of their trial, but he also went so far as to suggest that they should be deprived of the right to a lawyer. This seemed to be an effort not only to refute the presumption of innocence, but also to establish the opposite presumption (their guilt), which –by virtue of their deprivation from the right of defense– becomes irrefutable. And while the investigating judge in Tripoli Naji El Dahdah insisted on elaborating the indictment decision in order to justify exonerating the youth of the crime of rape as the case had become a public affair, the media generally remained silent following the issuance of this decision. The media provided neither self-criticism, nor a critique of the judicial ruling, whether positive or negative. Worse, Mokkadem continued firing off condemnations without going to the trouble of disclosing any of his evidence, and he did not hesitate to attack the indictment decision despite admitting that he did not read it.

The media’s second slip-up was its violation of the child’s privacy. It revealed her name and the details of the event that she experienced or reported that she experienced, which will exacerbate her stigma and the harm that she has thus far suffered.

This case is important because it completes the picture at a stage when the interplay between the judiciary and media is being strengthened. While the media has played and continues to play important roles guiding judicial work in the right direction, and enhancing the interplay between the judiciary and society, the practices of some outlets have shown the potential pitfalls of media misuse. These outlets overstepped the task of critique, monitoring, and guidance to the extent that they replaced the court trial and its rules that protect privacy, and the right of defense with a trial by media wherein sensationalism and demagoguery triumphed over all else. Thus, rather than constituting an additional factor and safeguard that deepens and rationalizes the discussion of social issues, here was the media undermining legal guarantees and exposing litigants’ interests to more risks and prejudices. This case is a valuable opportunity for the media to perform self-criticism in order to ensure its credibility, and affirm its role in enhancing the dynamism of its interaction with court cases, dynamism which we desperately need today.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

__________

[1] On this ruling, see The Legal Agenda, Issue No. 41.

[2] See: Lama Karame’s, “Lebanese Article 534 Struck Down: Homosexuality No Longer ‘Contrary to Nature’”, The Legal Agenda, Issue No. 39, May 2016.

[3] See note 1 above, idem.

[4] See: Karim Nammour’s, “The Ruling on Identity in the Beirut Criminal Court: Homosexuality and Privacy and the Regime’s Court’s Phobia of Them”, The Legal Agenda, Issue No. 42, August 2016.

[5] See: Joelle Boutros’s, “A Minister Rebels Against a Court Decision: This Airport is Mine”, The Legal Agenda, Issue No. 42, August 2016.

[6] See: Lama Karame’s, “The State Council Dismisses the ‘General Budget’ Case: The Concept of the ‘Popular Case’ as a Tool to Entrench Great Violations”, The Legal Agenda, Issue No. 38, April 2016.