Tunisia’s “War on Terror”: Security Tightens, the Judiciary Lightens

The Tunisian Constitution defines the judiciary’s function as follows: “the judiciary is independent. It ensures the administration of justice, the supremacy of the Constitution, the sovereignty of the law, and the protection of rights and freedoms.”[1] In characterizing the judiciary, the Constitution discusses values that promote human rights and the concept of a fair trial. Through its provisions, the Constitution strives to establish principles that enable the necessary conditions for the judiciary to fulfill its role, and states that “all kinds of interference in the functioning of the judicial system are prohibited”.[2] It establishes the Supreme Judicial Council as a constitutional institution that “ensures the sound functioning of the justice system and respect for its independence”.[3]

The dream of establishing an independent judiciary was a distinguishing feature of the Second Tunisian Republic. The Constitution established solid foundations [to that end] and safeguarded them, vesting political authorities with the responsibility to create institutions in support of those foundations. Thus, the Constitution specified that political authorities had no more than six months from the date of legislative elections to create the Supreme Judicial Council, and no more than a year from the same date to establish a Constitutional Court.[4]

It was anticipated that the judiciary’s responsibility to protect rights and freedoms would bring about legislative reforms to assist its fulfillment of that responsibility, and put an end to interference with its role which took placed under the First Republic. Likewise, it was expected that establishing the constitutional judicial institutions would be the easiest part of the complex mission of reforms.

Yet, political authorities failed to carry out this “easiest” of reforms. The constitutionally-specified period has lapsed, and neither a Supreme Judicial Council nor a Constitutional Court have been established. This constitutional violation provoked neither a political crisis, nor a broader juristic reaction. It was merely considered a lapsed deadline and nothing more. Meanwhile, the ratification of an anti-terrorism law was deemed an event worthy of celebration on the 58th anniversary of the declaration of the Republic. The growing terrorist threat –which, according to Tunisian President Beji Caid Essebsi, had come to threaten the stability of the state– made counterterrorism the fundamental priority of the Tunisian political regime.

The so-called war on terror was not responsible for obstructing the establishment of constitutional judicial institutions, or for opening up judicial reform to public debate. But the war seems to be the ideal cover for reassessing the position on the judiciary’s function as outlined in the Constitution. This reassessment of the judiciary’s role emerged from the security establishment, whose syndicates have promoted the slogan that “security tightens, the judiciary lightens”. The slogan points to the fact that the Tunisian judiciary released alleged “terrorists”, whose detention had put security personnel at risk.

The security establishment’s campaign led to accusations that the judiciary had failed to fulfill its role; its ”role” in this case, defined first and foremost as taking a hard line towards “terrorists”. The same accusation of complicity with “terrorists” was taken up by Bochra Belhaj Hmida, head of a parliamentary investigatory committee, in connection with accusations that a security unit had tortured individuals detained on charges of terrorism. In statements made to the press following her visit to the headquarters of the unit suspected of torture, Hmida, who is also a leading member of the majority ruling party, pronounced that “some judges lack the competence to investigate issues of terrorism”, and that “some of them represent a harm not only to the judiciary, but to the security of the country as well”.[5]

It was not just “some judges” as referred to by Hmida, that swiftly became the subject of a trial of public opinion in the media discourse on Tunisian national television. It was the judiciary itself which was depicted as the weakest link in the war on terror.[6] The media assessed the judiciary’s performance on the basis of narrowly-defined standards, including its release of suspects who had been detained by security forces and presented to the courts on terrorism charges. According to this logic, the judges who released them thereby enabled them to subsequently participate in terrorist operations and join terrorist groups.

Both official and media discourse quickly contained the shock arising from the accusation that members of a security unit had tortured detainees. Focusing on accusing the judiciary of its shortcomings in the war on terror was a way out of that crisis. That accusation has remained a constant in the speeches of the committee defending the assassinated politician Shukri Baleed, which views the investigating judge’s refraining from charging political officials as evidence of complicity with terrorism.

The phobia surrounding the war on terror has prompted discussions about the judiciary. In particular, discussions revolved around the latter’s insistence on investigating and confirming accusations before authorizing detention. Its investigation of allegations of torture against those detained in connection with terrorism have been cited as professional inadequacies, and evidence of incompetence.

Such an assessment reveals the receding importance of “protecting rights and freedoms” which the Constitution places in its framework for assessing the judiciary, in favor of demands that judicial work be brought in line with the requirements and work of security. The fear of terrorism has shifted the relationship between the judiciary and security: while this relationship was once in the realm of demands to strengthen judicial oversight of judicial police and crime labs, it is now tied instead to demands to strengthen coordination between security and the judiciary. All of this falls within a context in which the rhetoric of authority is calling upon the judiciary not to impede security efforts.

With the decreasing value of “administering justice”, bringing the judiciary in line with security has become one of the goals of the judiciary’s function, particularly when it comes to a particular class of crimes – those associated with terrorism. In this context, releasing those accused of terrorism is considered a professional error on the part of the judiciary, and one that threatens national security. This is, of course, despite the fact that Article 27 of the Constitution stipulates that “a defendant shall be presumed innocent until proven guilty in a fair trial”.

While it was once anticipated that the judiciary’s work during the first year of the Second Tunisian Republic would be judged according to its constitutionally defined functions, the political emergency has revealed that those standards of evaluation have been put aside to make room for the idea of “the judiciary’s success on security matters”.

Attempts to Impose Security Oversight on Judicial Decisions in Practice

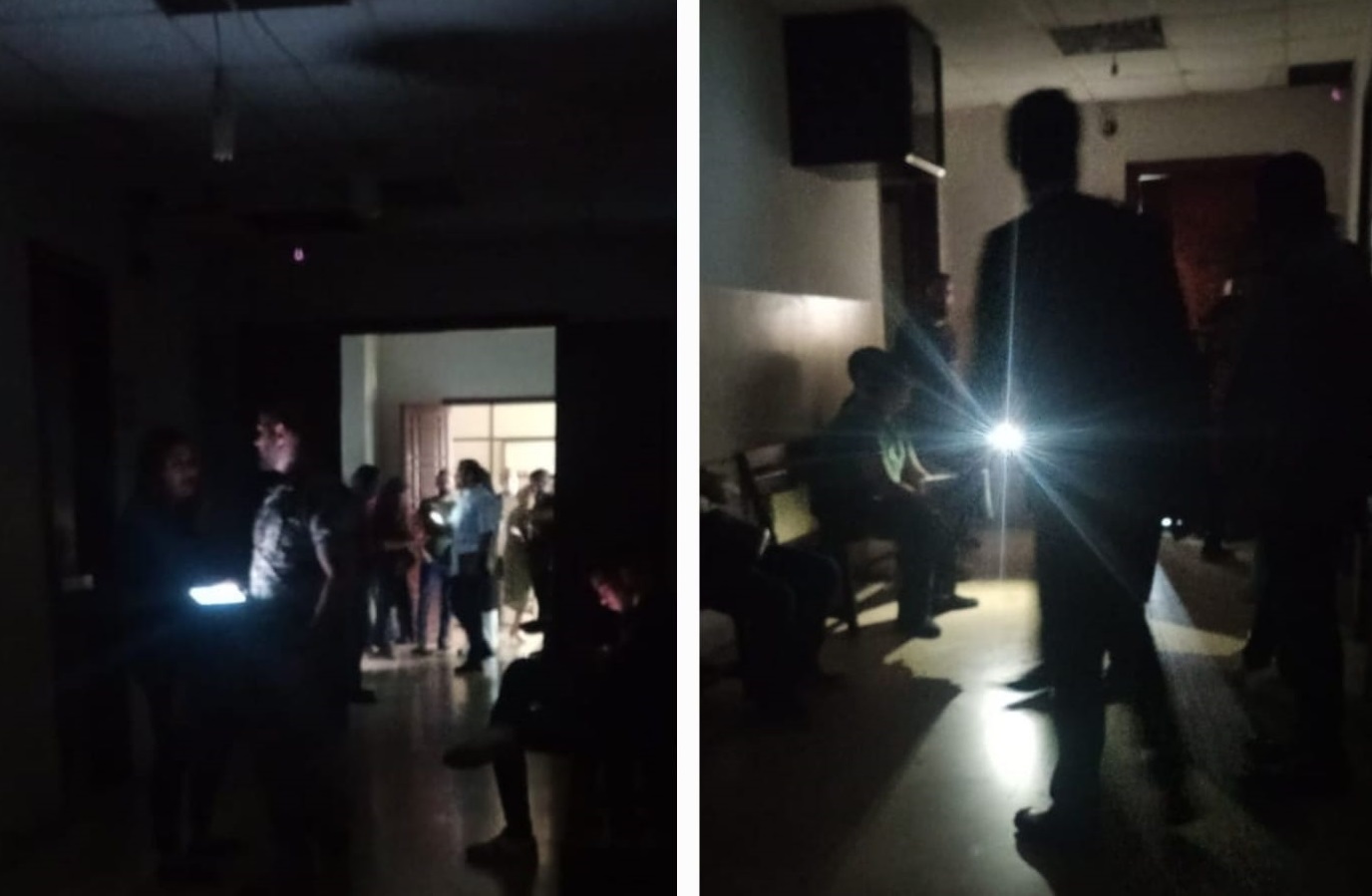

Rhetoric in support of a security approach to terrorism cases has spurred a faction of the security establishment to rebel against judicial decisions that are incompatible with the slogans of the security taking precedence over due process. On the evening of August 4, 2015, the investigating judge of the Court of First Instance in Tunis released seven individuals accused of terrorist activity. They had been delivered by the national counterterrorism unit and turned over to the public prosecutor of that same court. On the same day, an investigation was opened based on suspicions that the accused had been subjected to torture. Security personnel prevented the release order from being carried out, and the accused individuals were re-arrested and taken back to security headquarters. Security forces held the accused, without legal grounds, for five continuous hours, until the public prosecutor intervened. When told that new investigations had been opened into the detainees, he then authorized their detention.

The incident caused a crisis within the Tunisian parliament, which had planned to hold a plenary session that day. To address the crisis, they opened a parliamentary inquiry. While the findings of the investigative committee’s work were not publicized, its chair, Bochra Belhaj Hmida, stated emphatically that the accused persons had not been subjected to torture, and that the investigating judge had not done a sufficient job of investigating them, and thus had erred when he released them.

With this testimonial bestowed by the [political] authorities, security oversight of the judicial decision was imposed. On October 3, 2015, the same security unit re-detained an individual charged with belonging to a terrorist organization, whom the investigating judge had released from court headquarters. Again, the detention lasted five hours. This time, it seems that the public prosecutor refused to intervene in order to grant formal legal validity to the security intervention, and demanded that the unit release the detainee.

Political authorities failed to establish constitutional judicial institutions in the stipulated timeframe. By transforming the approach to the judiciary’s function and the corresponding nature of judicial institutions, they seem to have found a response to the demands of those who fear the threat of terrorism.

Legislative Efforts Produce a New Understanding of Judicial Proceedings

On February 2, 2013, the Tunisian government presented a draft law to the National Constituent Assembly. The law’s aim was to revise the Code of Criminal Procedure, reforming its statutes and bringing them in line with the requirements of a fair trial and an independent judiciary.[7]

The draft law aimed to place the work of the judicial police under judicial oversight, and stipulated that holding suspects requires permission from a representative of the republic or an investigating judge. This was in contrast to the system that had been previously in place, which only required the police to inform the representative of the republic that they were holding a suspect after the fact. The draft also shortened the holding time to 48 hours, subject to only one extension by judicial order.

The draft law represented a reform of the justice system, through granting the president of the court with the sole right to select investigating judges. This differed from the dictates of the existing law, which granted that authority to the agent of the republic – that is, the public prosecutor. The draft law likewise took up partial structural reform regarding the relationship between security and the judiciary. It stipulated that both the criminal record and legal identification be subject to the supervision of the Ministry of Justice.

However, at the same time that the draft reform law was presented, the technical committees of parliament pledged to create an anti-terrorism law; consideration of the revision of the Code of Criminal Procedure was suspended. The Ministry of Justice chose to withdraw the draft law for further consultation. This cleared the way for the anti-terrorism law, which was addressing the same questions.[8] But rather than shortening the holding period, the anti-terrorism law extended it to five days, subject to two extensions. It also eliminated the idea of placing detention under judicial oversight, and retracted the granting of the the right to select investigating judges to the president of the court.

Terrorism has transformed discussions of the judiciary – from a discourse that subjected the judiciary to public opinion regarding rights and basic freedoms, to one that justifies the idea of exceptional judicial procedures for those accused of terrorism. Putting the judiciary on trial, and claiming it was in breach of its duty to coordinate with security in the war on terror, was among the first results of this conceptual transformation.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

__________

[1] Article 102 of the Tunisian Constitution.

[2] Article 109 of the Tunisian Constitution.

[3] Article 114 of the Tunisian Constitution.

[4] Article 148 of the Tunisian Constitution.

[5] Statement on the program “Midi Show”, Radio Mosaique FM, August 17, 2015.

[6] See: “Wa Lakum Sadid al-Nazar,” program on Tunisian national television, October 2, 2015. This program was tantamount to a trial of public opinion regarding the judiciary’s shortcomings on the war on terror; see the Ministry of Justice’s statement regarding the show.

[7] Draft law revising the Code of Criminal Procedure, http://www.legislation.tn/sites/default/files/01022013.pdf

[8] See “anti-terrorism” Basic Law No. 26 of 2015, dated August 7, 2015.