Egypt’s New Constitutional Path: A Minefield of Discord Between Judges and Lawyers

To date, the Committee of 50 responsible for drafting the new Egyptian Constitution has not resolved the heated conflict between judicial bodies over their jurisdiction in relation to cases of disciplinary action.

The Committee of 50 has also yet to address the judges’ demands which were put forward in writing, outlining the judges’ expectations of the new constitution. The lack of a decision is largely due to the exaggerated nature of the demands. Moreover, some of these demands would have been more appropriately aimed at the Judicial Authority Act rather than the Constitution.

A number of other disputes continue to burden the Committee of 50 and hinder its progress amid signs of a new crisis surfacing between judges and lawyers, over constitutional provisions pertaining to the legal profession. Judges demand that the Committee of 50 present these provisions to the Judges’ Club for a close examination and opinion.

Lawyers, however, maintain their right to a constitutional provision which consecrates the independence of their legal practice. This dispute is the latest episode in a long running conflict between the two professional wings of dispensing justice. However, what is the modern history of this conflict and the essence of its latest round? How can a potential escalation of this conflict be avoided?

Modern History of the Conflict Between Judges and Lawyers

The unfriendly climate between judges and lawyers is not an outcome of the [content] of the constitutional provision which lawyers wish to include in the new constitution. This provision is no different from the first provision of the Legal Practice Act of 1983, and the latter has not been opposed by judges. However, the judges are opposed to the provision as part of the Constitution. They wish to subject it to examination under the assumption that the provision grants immunity to lawyers akin to that given to judges, and that placing it in the Constitution will further empower lawyers.

Whenever a legal or constitutional provision is proposed, the long running conflict between judges and lawyers is renewed. Other triggers of the conflict include instances when a judge and a lawyer have a disagreement, or when proposed amendments to the Judicial Authority Law include provisions that compromise lawyers’ rights, or when suggested constitutional provisions relate to lawyers. While most individual cases of friction between judges and lawyers are usually contained, some escalate when each camp advocates for its own members, thereby pushing the dispute towards its crisis point.

The several draft proposals of the Judicial Authority Act have led to the resumption of several rounds of this long-lasting conflict. Among these rounds, the most significant took place after the revolution of January 25, 2011. At the time, the president of the Supreme Judicial Council established a committee headed by former judge Ahmed Makki and entrusted it with drafting a law to buttress judicial independence.

Angry statements regarding some provisions of the proposal triggered a crisis that was further stoked by electoral biddings, as well as the prevalent revolutionary climate at the time. Lawyers shut down courts preventing judges from accessing the court rooms and conducting hearings. The conflict did not subside until it was announced that adopting the draft law would be delayed until a parliament is elected.

The draft proposed by judges referred to lawyers as aids to the judiciary, contrary to what has been determined by the Legal Practice Act. The proposed draft also granted judges a share of fines and judicial guarantees, thereby opening the door to circumventing principles of transparency in judicial appointments. This is in addition to the inclusion of Article 18, pertaining to charges of contempt and judicial authority, and one that does not naturally fall under the Judicial Authority Act. Lawyers feared that judges could use Article 18 as a weapon against lawyers who disagree with them.

The Core of the Constitutional Dispute between Judges and Lawyers

The most recent constitutional provision proposed by lawyers lies behind the crisis that is about to reignite the conflict between lawyers and judges. It reads as follows:

“Legal practice is a free profession which, along with the judiciary, partakes in achieving justice and the rule of law. It ensures the right to defense, and is exercised autonomously by lawyers.”

This provision was stated, verbatim, in Article 1 of the 1983 Legal Practice Act, to which no one has objected. The truth is that the Legal Practice Act provides lawyers with much more than what the proposed constitutional provision provides. Article 1 s.2 of the Legal Practice Act states that “legal practice is exercised only by autonomous lawyers, independent of a superior authority other than their conscience and the law”.

However, it is the desire for turning such a right into a “constitutional” one, of which we have warned time and time again, that is being objected to. The abuse by some judges of their authority in their interactions with their “fellow” lawyers may justify such a desire.

The suspended 2012 Constitution had stated in Article 181 that “legal practice is a free profession, and is one of the pillars of justice, exercised autonomously by a lawyer who enjoys throughout his work [certain] safeguards. These safeguards protect and empower him upon commencing this line of work, as regulated by law”. Judges did not object to this provision, but they are likely to point out that they had objected to the 2012 Constitution in its entirety, because in their eyes, it was the Muslim Brotherhood’s constitution, not Egypt’s.

As for the provision proposed by lawyers of the Committee of 50, it has angered judges as well as elicited reactions and commentaries that, in turn, provoked lawyers. Some judges have declared that the Committee of 50 must seek the opinion of the Egyptian Judges’ Club and the Supreme Judicial Council with regards to matters pertaining to lawyers’ immunity. The judges have justified that such a request be consulted by pointing out the complex and intertwined work relations between judges and lawyers.

To be fair, the proposed provision does not point to “immunity” for lawyers in the precise technical sense a constitution would normally speak of. It merely refers to immunity -in accordance with Article 109 of the Penal Code- against crimes of defamation and insult while conducting an oral or written defense in court.

As for the reference to a lawyer “autonomously” engaging in legal practice, it does not provide a lawyer with privilege, exempting him from the law or from responsibility for his behavior which may be criminalized by the Penal Code. The intended “autonomy” in legal practice, central to the proposed provision, is a requirement of free practice in which a lawyer engages. In order to protect the best interests of clients and every professional’s private life, a lawyer must be autonomous in his work.

A lawyer’s autonomy during legal practice is a professional necessity, which does not consist of immunity from legal accountability in the case that he does not fulfill the requirements of his professional duty. It is of no doubt that denying this autonomy elicits lawyers’ resentment, particularly given this denial was issued by a judge who demands -as this author does- that judges themselves be autonomous and belong to an authority which also enjoys autonomy.

The judges’ position on the lawyers’ draft constitutional proposal has elicited a wave of fury amongst lawyers that is not the first of its kind, and certainly not the last. This wave of fury began when the President of the Bar Association requested an emergency meeting to look into ways of responding to the judges’ objection. The meeting was held on November 6, 2013. During this meeting, the association’s president stressed that the “immunity” demanded by lawyers will not be as beneficial to lawyers as it will be for the accused. The president further emphasized that this immunity will be beneficial only at hearings and throughout investigation procedures, and that it will not resemble that of judges. He also stressed that lawyers have no categorical demands and do not demand extended immunities, but, they demand constitutional entitlements.

The president of the Bar Association also added that lawyers will not let their rights be undermined, and that they will not be caught in attempts to drive them into conflict with judges. He did, however, foresee confrontations in the days to come, due to the attacks that lawyers face in relation to their constitutional rights. These confrontations are likely to reach the Committee of 50 should the latter take the judges’ request into account.

What are the Future Prospects for Burying this New Discord?

It is inappropriate to allow the discord to escalate. Rather, it must be nipped in the bud. Siding with one camp against the other will not help resolve this crisis. For instance, on the morning of November 7th, newspaper articles written by jurists and constitutional experts spoke about the judiciary and their assistants, and opined that “the most important of those assistants are lawyers”, therefore referring to lawyers as “standing judiciary”!

Holding reconciliatory meetings will not end the discord, for these encounters mostly tend to deepen the dispute and intensify the impasse. Improving relations between both branches of justice is more about resolving the root causes of the tension between the two sides. This may take time, but if the process begins in earnest, the effort might bear fruit in the medium run. The proposed provision is a mere trigger for the precipitated ill feelings brewing under the surface. Therefore, it is necessary to find the reasons behind the mounting anger in order to achieve a full and speedy reconciliation.

What is now needed is an examination of whether the proposed provision should be incorporated into the constitution by the Committee of 50, whose membership includes unbiased judges and jurists. This author fears that this matter will be left to either party of the dispute to resolve it on their own. It is unfitting that judges wage battles other than their battle for autonomy and improving their efficiency, for they are one of the state’s authorities that govern by the rule of the law, and there must be no dispute between them and other groups in society.

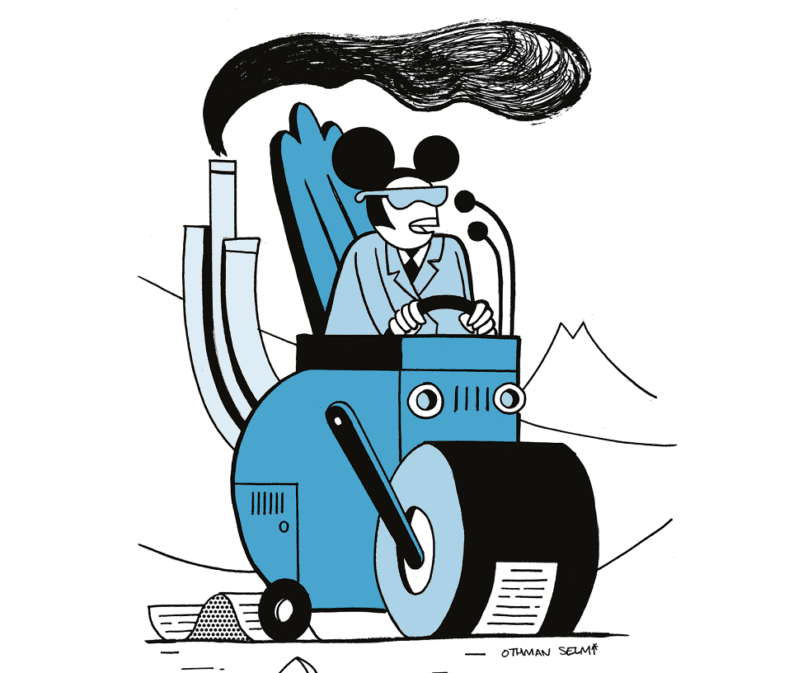

On the other hand, lawyers need not go further than embrace the provision special to legal practice as stated in the suspended 2012 Constitution. That provision is sufficient to guarantee the autonomy sought by lawyers. Each of the parties attempting to gain a proposition or advantage in the new constitution must be fully aware that saving the country from this setback is more important than any share, whether small or large, in the “Constitutional Pie”.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.